How Test-Driven Development Creates Code That ALWAYS Works (With Real-World Examples in Go)

A terrifying amount of the software that we use on a daily basis—from our phones to our fridges—has been developed poorly, under severe time and budgetary constraints.

The result is a badger’s nest of rotten code, held together by layers of patches and undocumented hacks.

It’s not a question of if these fragile systems fail, but when.

These fragile systems cost the US economy $2.1 trillion dollars last year.

As the systems start to crumble, more and more engineering time is consumed chasing and fixing bugs. As budgets become consumed by spiralling maintenance costs, innovation and development of new features can no longer be prioritised - leaving organisations struggling to keep up with the competition, rather than effortlessly staying ahead.

We need to change how we develop software: how we write it, what we put our confidence in and how we define what the software does.

In this blog I’ll be talking about a fundamental practice of software engineering that tackles just that: test-driven development (or TDD).

I’ll cover:

- What is TDD?

- Why TDD is awesome at maintaining long-term feature velocity

- How it differs from ‘traditional’ development

- Real-life examples of TDD using Go

What Is Test-Driven Development?

Test-driven development or “TDD” (not to be confused with BDD)is a rigorous method of writing software that focuses on first writing failing tests to clearly delineate the function of a given piece of code and then writing the leanest slither of code possible to pass the test.

The goal of TDD is to end up with the minimum amount of code necessary to complete the tests you laid out to fulfil your requirements and to be able to refactor with confidence.

It allows for high-quality, long-lasting systems that are incredibly stable and easy to change.

Why You Should Have Started Test-Driven Development Yesterday

Traditionally, software developers shape the code around the problem they’re trying to solve. They work the code, like clay, until they have confidence it behaves as expected.

While this can work in the short-term, when it comes to updating and maintaining the code over long-term it creates problems:

- It’s not always clear what the expected outcome of a given piece of code is

- Nor is it clear how integral the code is to the systems behavior as a whole, which makes it easy to break something when making changes.

Any future attempts to change, update or remove code then becomes very difficult.

Over time a series of hacks and patches are required to keep production code working, which ultimately makes the code more fragile and continues pain.

The genius of TDD is that it forces the developer to define the problem in the form of a ‘unit’ test before developing the functionality (solution). A unit test focuses on “individual units (modules, functions, classes) in isolation from the rest of the program” (Kent Beck). These tests live inside a ‘test suite’: a separate code base from the production code.

By writing the tests first, the purpose of any future chunk of code is clearly defined in advance (and for any developers who might update your code in the future).

Any change to production will instantly be put through the test suite and anything that breaks the system will be instantly flagged and prevent the faulty code from reaching production. This stops people making changes and just assuming that it’ll be fine.

This is especially appealing to developers as code that has been verified to work stays working as the tight feedback loops capture errors before they get expensive.

This brings us to the key insight: TDD rocks because it shifts your mindset.

You go from hoping your code works to knowing that it works. And this makes all the difference in the world!

Your confidence moves from your production code to your test suite. Most people fawn over their production code, but the test suite is what’s most valuable because it is the only way to PROVE that your software works!

Once a team has total confidence in their test suite they will be able to develop at speed, which means value is delivered to customers at a greater pace.

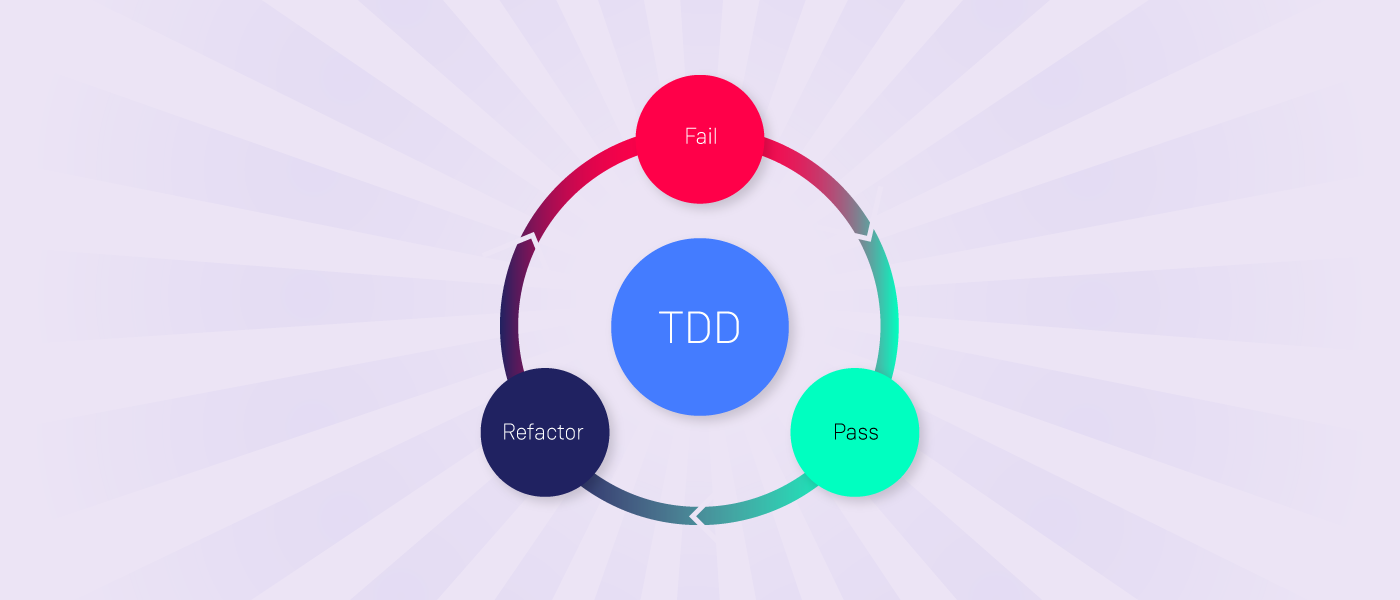

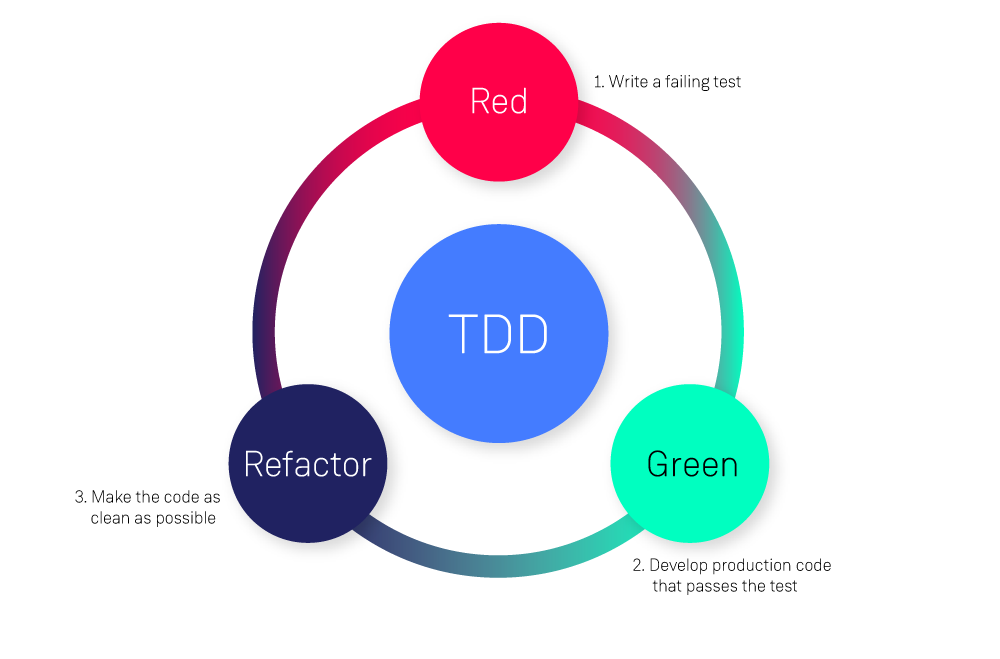

The Three Stages of TDD

There are three stages that your code passes through on its TDD journey.

1. Stage Red

The first is Stage Red: where you write a failing test.

The unit test should initially fail, because the functionality it is testing does not exist. Failure is a good thing: a failing test ensures the problem is clearly framed inside the developer’s mind and that the functionality that is to be written is documented upfront, with defined boundaries for the scope of the solution.

Sometimes you’ll write a unit test expecting it to fail and it passes. This is also good: it stops you progressing to the next stage (avoiding unnecessary duplication of work) and forces you to reframe the problem by writing another failing test.

2. Stage Green

The second is Stage Green: where you develop production code that passes the test.

Once the solution itself is developed, and the test passes, the developer knows that the software solution behaves exactly as intended.

3. Stage Refactor

The third stage, blue, is when you refactor the code to make it as clean as possible.

During this phase the developer can switch from making effective code - that behaves as needed - to code that is leaner, more efficient and safe to extend.

The result of these stages is code that has been sliced up into the simplest functionality possible that meets the requirements. The engineer also needs to think iteratively, to make sure that these small steps are producing useful software. At the beginning this could be something as simple as dealing with degenerate inputs.

Breaking down large problems into small, iterative chunks is a tricky skill to master but, with practice, it becomes second nature. The traditional cadence dissolves to become a series of tiny - circa two-minute - Red/Green/Blue feedback loops.

The process embodies the expression ‘go slow to go fast’. Yes, you may be able to type production code quickly but, as the codebase sprawls, you will need to coax it into behaving correctly numerous times - eating up valuable time. Similar to turning a ratchet with very fine teeth, test-driven code continuously moves forward as the developer is never more than a few minutes away from a solution with the intended functionality.

Now let's apply this to some code...

In the first part we went over what TDD is and it’s immediate and long term benefit. Now, let’s put on our code goggles, roll up our sleeves and test drive some code. In these examples I’ll be using Go. This should hopefully be easy to follow for everyone as it’s a concise language that does a great job of expressing it’s intent.

Exemplifying The Laws of TDD

We already saw the three laws of Test Driven Development that build on the simple Red/Green/Blue premise.

These can be a little hard to understand at first, so let’s step through each along with an example.

So the first rule:

Law #1 You are not allowed to write any production code unless it is to make a failing unit test pass.

This is pretty straight forward: always write the unit tests first.

As an example: let’s create a method that adds two numbers.

We first should create a succinctly-named test inside the test suite that follows the simple structure of:

- Arrange: set up the solution for the test (e.g.: create an instance of the class to be tested)

- Act: execute a function in the solution

- Assert: check the output from the function in the solution against an expected result

// Language: Go

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

// Arrange

calculator := Calculator{}

want_small := 2

want_large := 2468

// Act

got_small := calculator.Add(1,1)

got_large := calculator.Add(1234,1234)

// Assert

if got_small!=want_small{

t.Errorf("Small numbers didn't add correctly. Got %d, want %d", got_small, want_small)

}

if got_large!=want_large{

t.Errorf("Large numbers didn't add correctly. Got %d, want 2468", got_large)

}

}The above code has two assertions, which violates the second law:

Law #2 You are not allowed to write any more of a unit test than is sufficient to fail; and compilation failures are failures.

This Law feels purposefully restrictive when you first read it, however it’s intent is to help focus the developer in the current problem space. It encourages the lean ‘flow’ previously mentioned by forcing the developer to take small focused steps forward. In the above example we’ve jumped ahead of ourselves by testing both ‘small’ and ‘large’ numbers. Let’s fix that:

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

t.Run("Small positive numbers", func(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

want:= 2

calculator := Calculator{}

}The test fails as we’ve not defined the Calculator. This often happens when we’re testing a new class in languages like Java/C#. Following Law #3:

Law #3 You are not allowed to write any more production code than is sufficient to pass the one failing unit test.

We create a Calculator struct...

type Calculator struct {}...which, as the test has no assertions, makes the test pass. Now, following Law #1 and #2 again, we write the smallest amount of test code possible to fail:

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

t.Run("Small positive numbers", func(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

want:= 2

calculator := Calculator{}

// Act

got := calculator.Add(1, 1)

// Assert

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Didn't add correctly. Got %d, want %d", got, want)

}

})

}Compared to the first test, this unit test is easier to understand and maintain by testing just one thing well.

Back into the production codebase: as we are just creating an Add method, following Law #3, our solution should be as simple as the following, right?

func (w *Calculator) Add(a int, b int) int {

return a+b

}Not quite. The problem with the above method is that it does not reflect the true intent of the test in the simplest and leanest-possible manner.

The unit test is testing a method that expects two integers (1 and 1) and returns the total (2). Although the method is named ‘Add’, our production code should reflect the test assertions, not the ‘final solution’ we may already have in our minds.

Whilst working in such steps may sound strange, it allows us to solve hugely complex problems one small step at a time, removing the opportunity for subtle mistakes that are caught only in Production. This is similar to driving in a low gear: our engine does not struggle even when going up the steepest of hills.

This is what we refer to as ‘sliming’.

‘Sliming’ (a term coined by Gary Bernhardt in a `Destroy All Software` episode), is a less well-known expression, but holds the same meaning as ‘faking it until you make it’.

Sliming is a behavioural technique that software developers following TDD use to organically grow algorithms in a way that eliminates assumptions and unnecessary functionality.

Like beginning to learn the fundamentals of TDD, it initially feels counterintuitive as it requires the developer to have faith in a process over an immediate solution.

Sliming in Action

Our goal in sliming is to write the most minimal, hard-coded, purposefully-stupid code possible to make our tests pass.

This sounds and feels counterintuitive, however, if we have faith in and follow the process not only will the code remain lean, but, as we’ll demonstrate, our tests will provide us with such confidence the production code base will become a secondary concern.

So, to continue the simple ‘Add’ example: if there’s a method called ‘Add’ that only has a single test for ‘1+1’, we should first force the ‘Add’ method to return a 2 rather than implement the full addition logic.

func Add(a int, b int) int {

return 2

}Whilst this allows our unit test to pass, it obviously is not yet ready for production.

To take our first step towards production-ready code, let’s expand the unit tests to be more fully representative of the possible real inputs. Let’s check that the method supports adding two larger numbers, such as 1234 and 999:

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

// Note: Removed “Small positive numbers test” from example for brevity

t.Run("Large positive numbers", func(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

want:= 2233

calculator := Calculator{}

// Act

got := calculator.Add(1234, 999)

// Assert

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Didn't add correctly. Got %d, want %d", got, want)

}

})

}Once again, let’s slime the production code into passing the test:

func Add(a int, b int) int {

if a == 1 && b == 1{

return 2

}

return 2233

}

If there was only a single test for ‘Add’ - as can be normal behavior outside of test-driven teams - we could have easily assumed that all the common behavior we associate with ‘Add’ has been written and is working.

This assumption - and any confidence that comes with it - is misguided. A single test can only test a small set of execution paths in the code, and leaves a void of code untested. The code inside this void can rot and change behavior with nobody noticing, as we often see when there are only a handful of Acceptance Tests that do not catch bugs before they reach Production.

In the example above, we’ve written production code that mirrors our tests. If we continue down this path, we will just end up with a giant switch statement that is a 1:1 reflection of the test assertions. Another frequently used mantra to keep in mind:

“As the tests get more specific, the code gets more generic”.

In other words, as we write more tests we have to imagine a broader, more generic, solution in order to cater for the range of requirements. To demonstrate the meaning of this, let’s write, a third test for a negative and a positive number:

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

// Note: Removed “Small positive numbers” and “Large positive numbers” tests from example for brevity

t.Run("Negative and a positive number", func(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

want:= 110

calculator := Calculator{}

// Act

got := calculator.Add(-10, 120)

// Assert

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Didn't add correctly. Got %d, want %d", got, want)

}

})

}What is the smallest change to our solution code that behaves as the three tests expect? How about this:

func (w *Calculator) Add(a int, b int) int {

returnNumber := a

for i := 0; i < b; i++ {

returnNumber += 1

}

return returnNumber

}The code now caters for all inputs and behaves like a generalised algorithm.

What we’re starting to see is the logic naturally evolving through a series of behavioural transformations. ‘Behavioural transformation’ is a bit of a mouthful, but is just the small changes we see in the solution (behaviours) as they are gently nudged toward more generic functionality by a growing number of tests.

A behavioural transformation could be as simple as a constant being changed to a variable, or (as we can see above) an `if` statement becoming a ‘for’ loop. The process iteratively evolves the code into its final shape, whilst retaining its tested functionality.

Different people will have different assumptions about what an ‘Add’ function should do. If documentation is limited or out of date and confidence in the test suite is low we naturally lean on these assumptions more. One person may only wish to add positive numbers, the other may not.

In the above example, the three tests pass. The only thing we know, for certain, is that it does these three things. We should not assume it does anything else like, for example, two negative numbers:

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

// Note: Removed “Small positive numbers”, “Large positive numbers” and “Negative and a positive number” tests from example for brevity

t.Run("Two negative numbers", func(t *testing.T) {

// Arrange

want:= -20

calculator := Calculator{}

// Act

got := calculator.Add(-10, -10)

// Assert

if got != want {

t.Errorf("Didn't add correctly. Got %d, want %d", got, want)

}

})

}The test fails: “Didn't add correctly. Got -10, want -20”.

It looks like the algorithm does not work as expected when adding two negative numbers.

What’s the smallest change we can make to make the tests pass? How about shifting that fixed ‘for’ loop towards a more traditional ‘while’ loop behavior and moving to bitwise operators?

func (w *Calculator) Add(a int, b int) int {

for b != 0 {

carry := a & b

a = a ^ b

b = carry << 1

}

return a

}It works! Could this be a coincidence? To be safe, let’s add new tests to be certain: two 0s and, a wildcard, minus 0 and 123. To make the tests less verbose we could also tidy up to use an array of structs:

func TestAdd(t *testing.T){

// Arrange

calculator := Calculator{}

values := []struct{

a int

b int

want int

}{

{a:1 , b: 1, want: 2},

{a:1234 , b: 999, want:2233},

{a:-10 , b: 120, want:110},

{a:-10 , b: -10, want:-20},

{a:0 , b:0, want:0},

{a:-0 , b: 123, want:123},

}

for _,value := range values {

// Act

got := calculator.Add(value.a, value.b)

// Assert

if got != value.want {

t.Errorf("Didn't add correctly. Got %d, want %d", got, value.want)

}

}

}

The solution seems to behave exactly how the tests expect, but - interesting - it is certainly not what we’d expect to find if we looked under the hood of an Add method.

So the big question: who cares?

Well, with the current test coverage many developers wouldn’t care as it is behaving exactly as needed.

However, imagine if there were no tests (or just the first one for ‘2’) and a new developer stumbled across the Add method. They might find that the method does not demonstrate its intent clearly and it’s hard to read, and therefore maintain. This would be even worse if we lifted the hood and found the first ‘for’ loop that didn’t work with negative numbers!

This process has shifted trust from the production code onto the test code, which is exactly where it should be. We no longer hope the production code works, we have confidence the tests prove the functionality needed.

This trust in the test code should be absolute and shared not only between team members but also the wider business. Everyone should know that when a unit test suite passes the software is ready for the production environment. Only when a team and a business is this happy with a code suite then it should consider automating deployment of software.

With that in mind, the above Add method could easily find itself in production. For many years it could be happily adding away until one day perhaps that new developer on the team decides to take a peek at it. They see the code could be easily cleaned up and quickly replaces it with:

func (w *Calculator) Add(a int, b int) int {

return a +b

}The suite of tests pass, the pull request is approved and the code merged into master. Once deployed, no users notice the difference. The code base has gotten a little bit better and everyone can sleep at night because they were able to confirm - with very little effort - that all their past functionality continues to work.

Summary

By sliming a simple Add method we’ve demonstrated how to step towards delivering the leanest, highly tested solution for our customers. The final end state of this solution was very different to our preconceptions, and that’s not a problem because we have confidence it works.

This confidence is well founded. Our tests reduce waste, re-work, and fear of change, by being granular enough everyone has confidence behavioural changes will be captured.

This shift in thinking - from hoping our software works as anticipated to knowing that it adheres to our tests - ripples outward causing many positive side effects: both the teams performance and health improve because they’re no longer building on sand. As delivery risk is reduced and quality improves the business accepts that the software they’re investing in no longer has a predefined lifespan, but is an integral and evolving part of the core business value offering.